Composing an end-of-season amaro

Making a bitter liqueur that paints a portrait of time and space

Years ago, when I lived in Seattle, I went to an exhibition at the Frye Museum that still haunts me, though I can no longer find the artist's name. The curators had filled one of the Frye's side galleries with small, banal objects mounted on the walls or displayed on pillars. I seem to remember a rattle, perhaps a few chess pieces.

It was impossible to tease out meaning from the objects themselves, other than the generalized aura of art-ness that their setting suggested, as if they were yet another Duchamp readymade. Then I leaned into read the display cards. The lists of materials used in each object's construction — usually something laconic like "resin" or "oil on canvas" — unlocked fantastical worlds: Powdered bone. Rose petals. Threads from baby blankets. To make each object, I discovered, the artist had ground together dozens of Gothic substances. It was as if they'd found a way to excrete their own memories into the physical world, or infuse the objects with discarded memories that they'd plucked from the gutters of the cosmic consciousness. I circled the exhibit again, reading each list of materials as a poem.

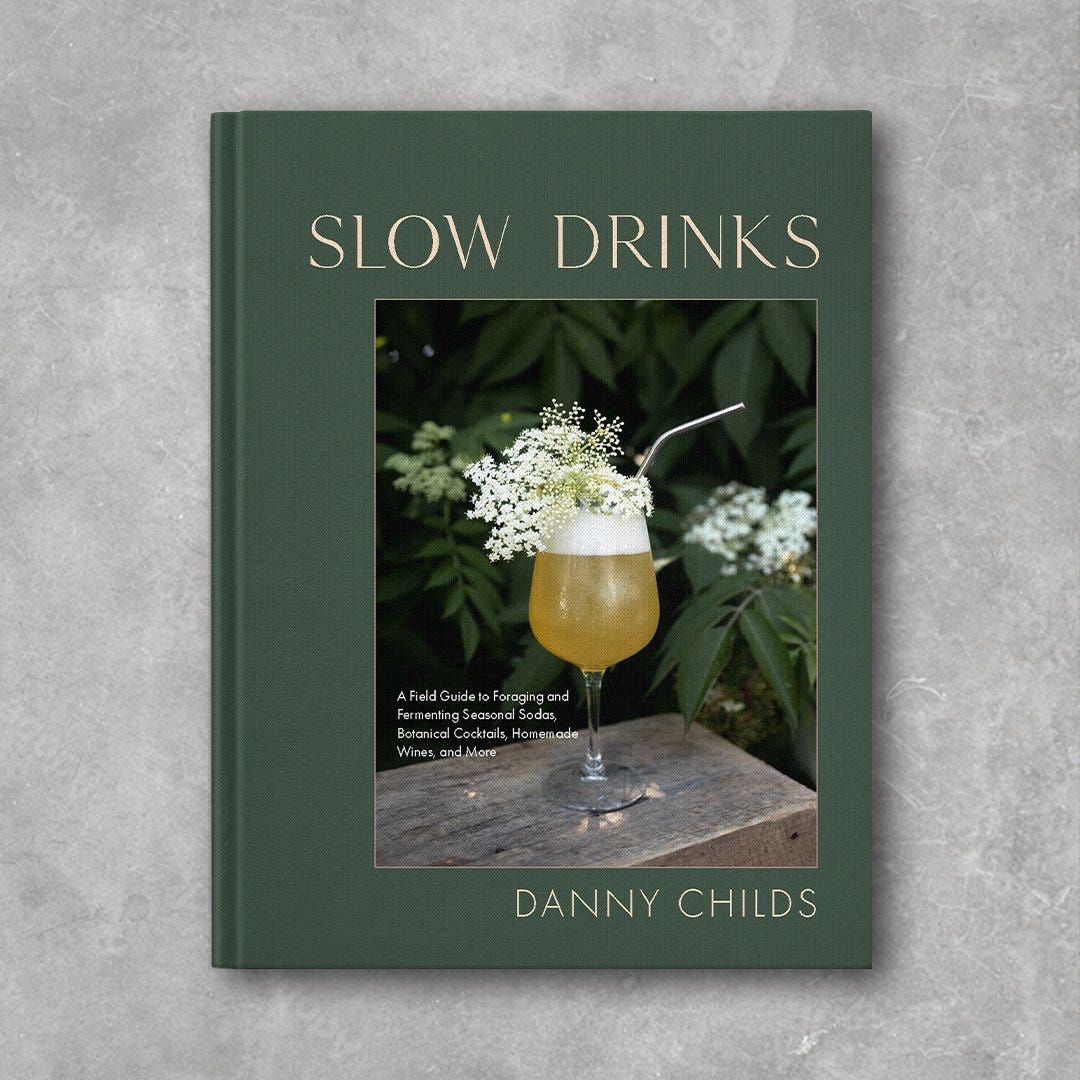

That exhibit came to mind last month (seriously, if you know the artist can you tell me in the comments?) when Hardie Grant, the publishing house, sent me a review copy of Danny Childs' new cookbook, Slow Drinks: A Field Guide to Foraging and Fermenting Seasonal Sodas, Botanical Cocktails, Homemade Wines, and More.

While earning his master's degree in ethnobotany, Danny spent several years in South America conducting field research in indigenous communities before moving to the Philadelphia area and managing the bar program at New Jersey's Farm & Fisherman Tavern.

Though many of the foraged ingredients in Danny's recipes are more common to the East Coast and Midwest, I read Slow Drinks as an inspiration book for future projects. The recipes that took strongest hold of my imagination were the book's four seasonal amari—bitter digestifs made by infusing clear spirits with a dozen or more botanicals. His spring amaro includes spruce tips, rhubarb, horehound, and roasted dandelion root. The alpine-style winter amaro brings together pine needles, sumac, birch bark, and juniper berries. The recipes conjure up aromatic odes to time and place.

I called Danny to ask him how he came up with complex infusions like these. After studying Amazonian ethnobotany and indigenous medicines, he told me, when he returned to New Jersey and started working behind a bar he noticed that every bottle, every syrup, every liqueur, began with plants. "I started a Google Doc and began to type in where the plants came from," he said. "What was the cultural significance? How do we use them now? How can I mimic these flavors or find them locally?" Then he headed into New Jersey's wild spaces and the restaurant's gardens, and spent years documenting his efforts and the cocktails he produced.

The amaro tests began after Danny read Brad Thomas Parsons' Amaro, which includes a make-your-own-amaro recipe based on traditional European herbs and Asian spices. "The way that amaro or vermouth was originally made was a way of preserving the things that grow around you," Danny says he realized. These drinks were designed to heal, not to stir together with bourbon and an orange twist. "Then the spice trade happened, and the trading companies were bringing back new flavors that were delicious and novel so they became staple ingredients in amari. Really, it was about going back to how [an amaro] was made in its earliest form, but filtering that through the lens of where where I live."

After years of testing out flavor combinations—"I never threw out a batch," he says—he settled on proportions that seemed to yield the best results. Slow Drinks classifies botanicals as bitter, acidic, herbaceous, sweet, spicy, floral, and deep. Amaro makers like me who want to adapt his recipes to their own landscape need to balance out those qualities in their own infused spirits.

In the weeks after I read Slow Drinks, I wandered around my lawn and neighborhood, gathering ideas for a North Portland Fall 2023 amaro. I toasted the noyau (inner pits) from a neighbor's plums, which Danny's book instructed me to double-roast to bring out the seeds' nutty flavor while neutralizing cyanide-forming compounds. With the owner's permission, I picked a Seville orange from an improbably large—improbable, period, in our climate—orange tree that grows a half-mile from our house.

In late October, the weather report forecasted the year's first frost, and so I headed out into the yard with my snippers. From the herb beds, I cut off sprigs of tulsi, rosemary, fennel flowers that had gone to seed, savory (because it has become my defining herb) and yerba buena (because it is San Francisco's). Then I filled a basket with plants that were about to die:

Sprigs of mugwort (a relative of wormwood, a common amaro bittering agent) from an overzealous plant I planned to cull from the garden

Fig leaves from the suckers I needed to remove

Late-blooming lavender and marigold clusters

The most vividly colored rose hips from our bushes

Bright-red flowers on a tangerine sage bush that the hummingbirds still visited

A spray of yarrow flowers that a rabbit had lopped off the night before but never devoured

As I arranged petals, herbs, seeds, and two farmers-market apples, in a clear glass jar, it felt as if I were casting an incantation, a spell to preserve the last of the summer sun. Then I dipped my nose below its lip, inhaling the resins from the orange and mugwort, attempting to conjure up the aromas that alcohol might unlock from the fig leaf, yarrow, and roasted plum pits. I puzzled over how these fall smells would fit together. How they might create something layered and mystifying and new.

I poured a liter of high-proof fruit brandy into the jar of aromatics, labeled it, and set the concoction in the basement for five weeks. In another week, I'll strain out the infused brandy. Slow Drinks suggests two possible uses: I could add sugar and water to this high-proof tincture to create an amaro for sipping, or I could stir a small amount of this spirit and some sugar into white wine to make my own vermouth. I'll probably try both, then spend the rainy months dreaming of a new incantation, an amaro to spell away winter and speed the return of spring.

I honestly thought I was going to do this for about five minutes. I make sloe gin every year. But then I read the list of ingredients you came up with and sat back down again. I did pour myself a glass of a new Edinburgh amaro, I think it’s flavoured with clove and orange peel, bless their simple hearts.

Wow, I would love to hear how it came out. I used to have some of these herbs living in Santa Rosa, CA. Where I live now I manage with some wort, which survives the heat of the summer here, over 100 degrees Fahrenheit. I have basil year around, and got some kale and kohlrabi for winter. A lot of herbs were once preserved in spirits and used as medicine, or dried and stored, since a lot of them are not perennials. When I took an herb class in Forestville, we learned how to do tinctures, mostly with alcohol, to preserve the properties of the herbs. You can look it up what the herbs you put in your concoction are good for your health, besides the interesting taste they will give to it. Maybe you can make a new amaro for every season, what do you say?