This June, my front yard was covered in masses of pink, purple, and golden flowers. The farewell-to-spring and the Grosso lavender spilled so far over the driveway that we’d wade through blooms to get into the car. But by September, the clouds of pink had withered into a stubbly brown thicket.

For a few months, I let the wildflower corpses languish. I'd pass along the yard, buffeting them about with my hands, hoping to shake the seeds out from their seedpods. As the rains approached I gradually ripped out the dead plants or, if they had hollow stems, clipped them down near the ground in case pollinators were looking to shelter in the tubes. The last to go are to tufted bunchgrasses, the only plants that look as if they had intended to be attractive in death.

Now that the yard is finally, actually going wild, it's clear I've got some editing to do to break up the monocultures I’ve seeded and ensure the plants evolve with the seasons. More late-blooming native wildflowers. More perennial herbs and vegetables that I can harvest through through the fall. Our woodchips are breaking down into good humus, and the wildflowers are just as eager as the weeds to gentrify this newly cleared land.

As autumn has taken hold, and my own lawn has gotten scrubby, I've found a new appreciation for the shifting colors of a larger rewilded meadow: the lands outside the Zen temple where I sit. Most of Dharma Rain's 14 acres, a landfill that was capped in 6 feet of soil after the facility closed in 1982, are covered in thigh-high grasses and flowers. The trails threading through the grasses are a popular dog-walking destination for the neighbors.

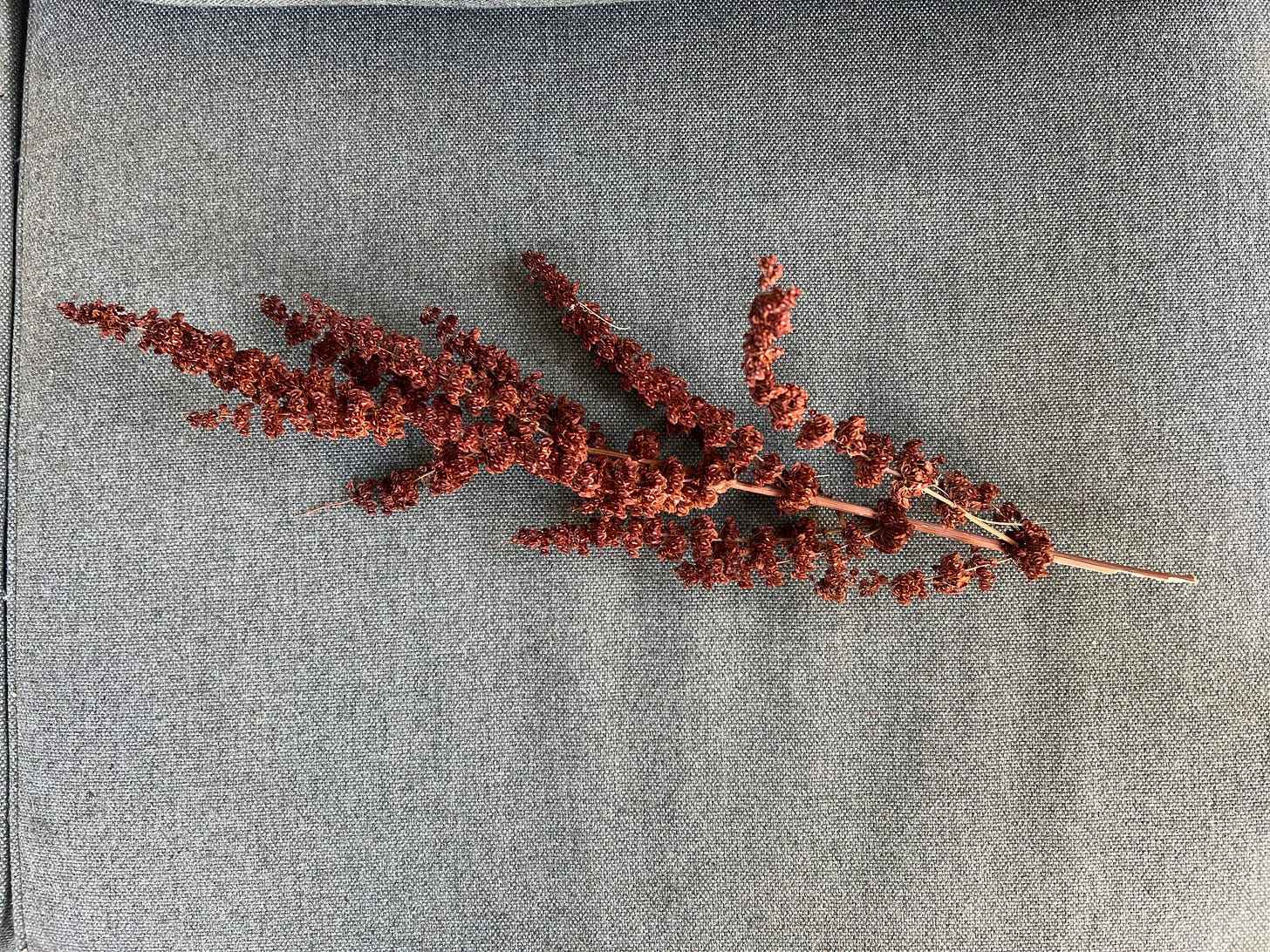

Over the decades the plants in this meadow have grown together, the invasives and natives have found a balance, neither side pushing the other out. This year I've been admiring the native tarweed, or common madia — which looks like a child’s drawing of a sunburst — and the invasive periwinkle-colored chicory blooms, which only open in the morning. As the spring flowers have died away and the grasses have gone golden, the beauty of another weed has emerged: the oxblood seed clusters of curly dock.

Curly dock — Rumex crispus — is one of those urban foraging projects that the experts recommend to beginners. Whether you're consuming the spring greens or the fall seeds of this prolific weed, it is safe, ubiquitous, and visually distinct. All over North America you can find curly dock in gardens and roadsides, meadows and playgrounds.

But before dock seeds snuck over to North America on ships and scurried across the continent, bedeviling gardeners and displacing native grasses, dock was a wild food in Europe. More than that, perhaps: a staple food.

Dock seeds have been found in neolithic sites across the continent, in the fossilized sludge at the bottom of fire pits as well as the stomachs of bog bodies. Indigenous Europeans have been gathering and eating dock seeds before wheat and barley displaced them from our diets, except perhaps during times of famine.

Even as I was figuring out what I wanted to make with dock, I flipped through a cookbook published in Serbia and spotted two recipes for dock leaves. One, a variation on dolma, rolled chard-sized, mature dock leaves around rice and aromatics. In Serbia, dock may be a food gathered from the edges of fields and roads, but it still is not a weed, at least in the way Americans use that word.

I asked a few temple residents whether I could gather dock seeds from the meadow, and one showed me the container of dock flour she had already gathered and ground herself. On a sunny afternoon, I waded into a thick stand of grass, glove on one hand and a trash bag in another, to knock the seed clusters off their stems and into the bag.

It took so little time to gather 4-5 cups of seeds that I had no time to soak in the pleasure of the early-fall sun or the tips of the grasses brushing at my arms. But there's no point taking too much when you don't know what you'll use, and I didn't want to rob the meadow of such a beautiful weed. I brought the seeds home, rubbed handfuls together loosely, then picked out the bits of stem and leaf. Once I ground the unhulled seeds in a spice grinder, the 4 cups condensed down into a scant half-cup of rust-colored flour.

Several weeks later, I baked up a loaf of my house bread — I just wrote about my love for Ken Forkish's recipe for Eater — with 25% WSU climate-blend wheat flour and 5% dock seed flour. That's the same proportions I would use for dock's relative, buckwheat: just enough to flavor the loaf without blunting its rise. Even that tiny proportion of the flour turned the loaf purplish brown.

I wish I could tell you I loved the dock bread. But something about its grassy flavor resembled an unresolved seventh chord. It needed some other flavor to complete it. Perhaps dock flour belonged in pumpernickel bread, cosseted by the richness of molasses and dark beer. I warmed to the flavor only when I began making sandwiches, and dock's tannic nuttiness resonated in sync with the bitter vegetal prickle of lettuces, as if I’d seasoned the sandwich with a few extra twists of black pepper.

Next year I may give dock flour another go. Considering it may have kept my ancient ancestors alive, it deserves another try, just to see if I can figure out where it wants to shine. I loved the look and color of the seed clusters enough to display them in a vase on our kitchen windowsill. I've even contemplated sprinkling some of the seeds over my patch of grasses and wildflowers to beautify next September's yard. Not going to do it, though. Probably not.

Something about the words "dock bread" makes me want to write a haiku, but I will spare you. ;) xo

Thanks for this well written and informative post. More please.