13. Quinces: Duty or Gift?

Fighting the languor that sets in when you have a bowl of ripening quinces

A quince, if you've never cooked one, is a puzzle: tannic and scratchy on the tongue when raw, hard to cut without a just-sharpened knife. For those of us who have figured out how to unlock the knobby fruit's fragance with gentle heat, a handful of quinces from a friend is a delight.

A tree full of quinces, however, is a duty.

Last year, when I started thinking about just how I could eat my neighborhood, I already knew quinces would come my way in the late fall and early winter. Several of my friends own quince trees—and every one gives fruit away.

Many of the projects I took on last year resembled thought experiments, or perhaps small rituals of appreciation—a dandelion salad from the yard, a few sips of tea from dried flowers I clipped off a linden tree. Others, like the 30 pounds of plums friends gave me to ferment, were so urgently ripe that I had to clear my schedule as soon as they came off the tree, spending the next two days in clothes that sticky juices couldn't permanently damage.

Quinces, which ripen languidly and fragrantly, impose a lazier duty. You can't just grab one off the table to snack on. A bucket of quinces can sit on the dining room table for weeks, radiating its cool, clean aroma. It whispers, "Just deal with this later" for so long that by the time you get around to it you've lost a third of the crop.

This year I was determined to mount a decisive attack. When Kevin and Sharon cleared their quince tree of fruit in October and sent me home with close to 25 pounds of fruit ("Oh, maybe take a few more"), I set aside the day afterward to make quince wine.

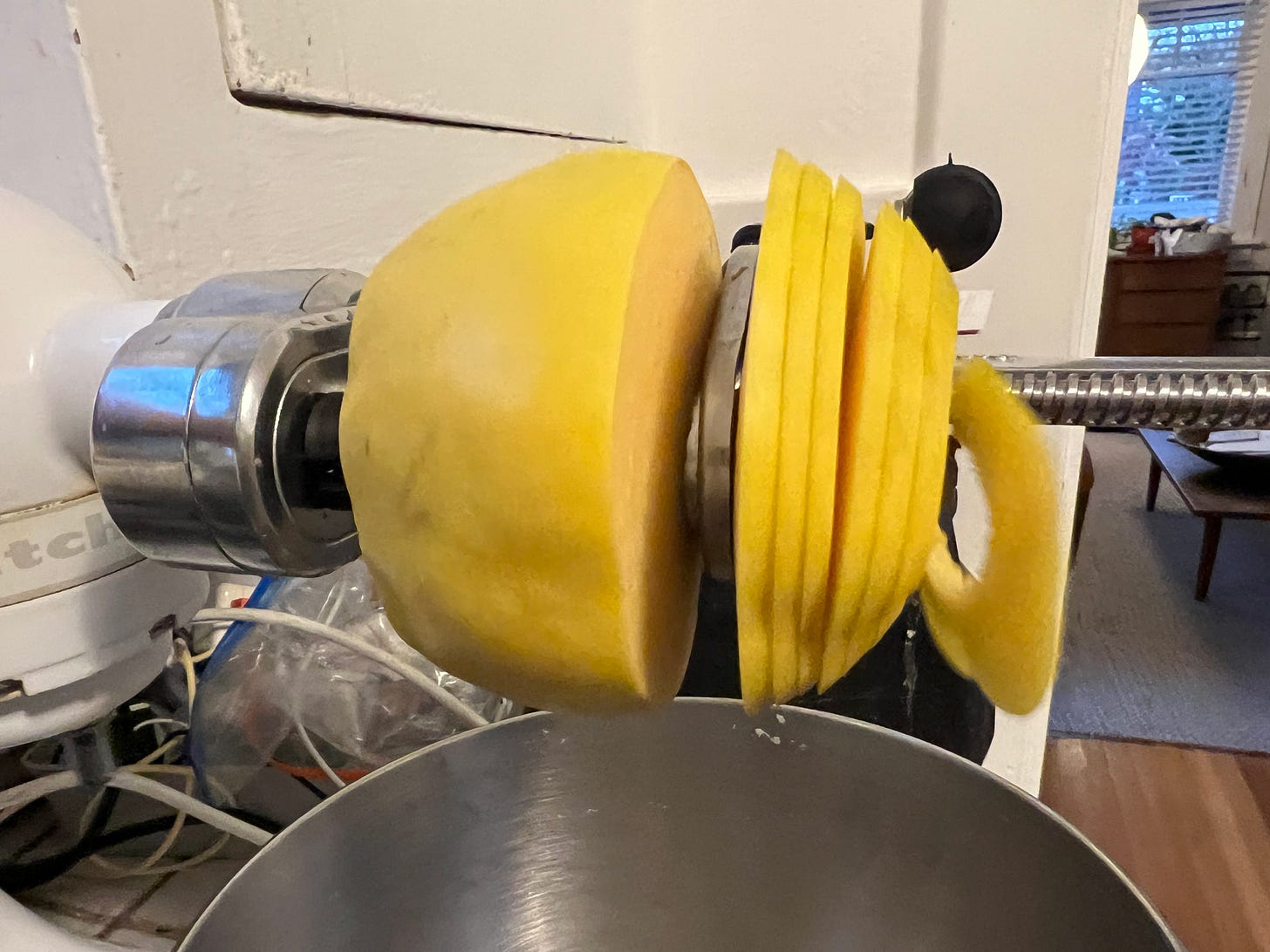

Most recipes start by shredding the quinces and cooking them just for a few minutes to break down the long chains of pectins that make up their cell walls, and so I used an apple corer-slicer KitchenAid attachment and then a knife t

o cut the hard fruit into strips while minimizing blood loss. I filled a 5-quart pot with shredded fruit, added just enough water to cover, then brought it up to a boil for 5 minutes, dumping each batch into a 6-gallon fermenter and starting the process again until the bucket was full. A little pectin enzyme, a little sugar and fruit-wine yeast, a few weeks of stirring and waiting, and I eventually had four gallons of low-alcohol quince wine. I could either rack and age it, or inoculate it with an apple-cider vinegar mother following Kirsten Shockey's recipe in Homebrewed Vinegar, or even double-distill it into quince rakija, if I were willing to break the law.

That took care of 17-18 pounds of quinces. The last third of the fruit sat on my dining room table, letting me enjoy their fragrance, for weeks. Then I couldn't resist an offer of more quinces from Koto, who had a table full of them in her back yard, and my remaining 7 pounds turned into 15. Rot set in, brown spots that swelled until they eclipsed the fruit's yellow rind. I threw away one quince. Then three more. The pile shrunk. The dread grew.

I began to ask myself: Does a gift ever fully belong to the recipient? To receive a gift is to feel responsible for enjoying it. To sense the tether of gratitude that connects you to the giver rub against the skin, tugging at you the farther you walk away. With an abundance of quinces, the debt I felt was not necessarily to the humans who had picked the fruit (though: a heartfelt thanks!), but to the trees that had spent so many months growing it.

In my own garden, aphids, heat, and ice ruin much of the produce I attempt to grow every year. To lose even more from my own inattention feels like committing an insult. I was so immersed in work this winter that I had to feed rotted chunks of quince to the worms in my compost bin, hoping that at least some beings could honor the trees’ gift. Now and again, I chopped up batches of fruit to blanch and freeze.

In mid-December, the fog of work cleared and I had time to take on the duty I'd taken on, gratefully, months ago.

The problem with too many quinces, most of the quince-tree owners I know have found, is that the easiest way to cook down too many quinces is membrillo, or Spanish quince paste. As delicious as membrillo is—and it is delicious—there are only so many cheese plates you can serve until the next harvest, and only so many friends you can give membrillo to. I learned that lesson 15 years ago, when a Seattle colleague brought me a box of quinces from his tree, and one year later I chucked the last squares of membrillo lurking in my fridge.

Instead, over the holidays I made quince pâtes de fruits, letting a block of pectin-thickened, sugared quince paste firm up in the dehydrator before cutting and rolling cubes in granulated sugar. Another five pounds of fruit went into Turkish quince preserves. Following Aysenur Altan's YouTube demonstration, I added quince seeds to the simmering fruit to help the liquid gel, and I amplified the floral aroma with a spoonful of pandan-flower water I had bought several months before, mistakenly thinking it was pandan-leaf extract (from a different Pandanus species).

Only then, with quince candies, quince preserves, and quince vinegar in the cabinets and a few bottles of quince booze aging away in the basement, did it feel as if I could set the responsibility aside. Boxes and jars have gone to some of the human givers, with more to give away. I have no idea how to apologize to the trees, however, for the fruit wasted. Perhaps a few worm castings scattered around their roots.

I honestly had never heard of a quince! Thank you for this introduction.

one line that really struck me: does a gift ever really belong to the receiver? Yes, there does always seem to be an obligation to enjoy the gift...

Oh my gosh, what wonderful creativity to use all those quinces! I wonder if a distiller would be willing to trade doing the distilling for quince wine...or other quince treats. Sounds like we need to go out and make friends with distillers! :)